Coin base is under construction

When the areas of Moesia and Thrace (now Bulgaria, eastern Greece, north-west Turkey) were administratively incorporated into the Roman Empire, they also had to engage in the cogs of a huge and complicated machine of economic ties, including, above all, a developed monetary system. The subordination of the entire Balkans by the Romans meant that the areas were also absorbed into this organism economically. The huge creation that was the Roman Empire was extremely diverse, which you should be aware of, but everywhere it was supported by the same element of the economy – coins issued according to strictly defined Roman standards applicable throughout the Roman world (4.5 million km2).

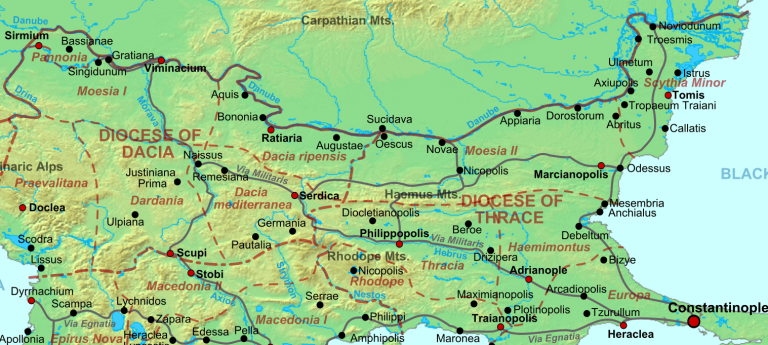

Coins in current circulation began to flow to the newly conquered Moesia and Thrace. This system was not entirely unified. Each of the provinces showed distinct local characteristics. This was also the case with Moesia and Thrace. These areas were initially poorly developed economically and urbanistically, but they played a huge strategic role for Rome. As many as four Roman legions were stationed on such a short section of the Danube limes. It was this aspect that influenced the intensive investments in the new provinces, e.g. the construction of roads, which had a huge impact on this area visible to this day. There was an avalanche of demand for „Roman” money there. In 86, Moesia was divided into two provinces. The situation in Upper Moesia began to develop differently than in Lower and Thrace. From that time until the end of the 2nd century, the monetary circulation in the study area was a reflection of the Roman system. Small amounts of republican coins and a sudden jump in the period when Roman provinces were created from the Danube areas are perfectly illustrated by the scheme of introducing an efficiently functioning instrument of the empire’s economics, i.e. coins, to local markets.

From the end of the 2nd century, the monetary circulation in these areas began to change dramatically. There was diversification of the monetary system in different parts of the country. Although for a long time the „bronze” coin of central issues (the Rome mint) had the advantage, but from Septimius Severus everything began to take its own path. On the „market” appeared „bronzes” minted in local, provincial mints, the issue of which increased exponentially, so that in the middle of the In the 3rd century, these coins took over the monopoly in monetary transactions also in the neighboring areas. The intensifying invasions of foreign peoples, internal unrest, and the economic crisis resulted in mass hiding of assets, mainly in the form of treasures that, for various reasons, did not return to their owners. Thanks to this, we have huge amounts of coins that will be used to reconstruct the monetary circulation in Moesia and Thrace. A small object such as a coin, in the juxtaposition of the entire circulating monetary mass, can convey extremely important content, revealing the image of human life in antiquity in many aspects: universal motifs, local motifs, local religious motifs, Roman religious motifs, economic development of the region, etc.

These provincial coins, specific to each province, played a huge role in the monetary system of the Empire. They supplied the local market with coins, and wages were paid in them. Provincial mints were very sensitive to political and military events. They were part of the Empire’s monetary system, but also reflected the identity ideas of the provincial population. Until the 3rd century, there were 30 mints operating in the study area.

We note the increased activity of the mentioned mints from sch. II century, but they started their activity earlier. What was the reason for their collapse and cessation of activity? Was it the deepening economic crisis in the 3rd century? Or the numerous looting raids that had a devastating impact on the economy of the war zones? Although we have a list of 3rd-century treasures, it is old and often undocumented.

One should look again at the old lists of finds from the discussed areas, as well as make new, supplemented, verified and analyze them in conjunction with data of a historical, epigraphic and archaeological nature, and in terms of technology.

The project proposes a new way of data analysis, examining provincial coins as an archaeological relic functioning in close dependence on historical and economic events.

The scope of research covered by the project is much wider chronologically and thematically. The next time period included in the project and set by the monetary system of the empire is the period from the monetary reform of Diocletian to the end of the 5th century, when, together with the reign of Anastasius, the coinage

has undergone significant changes. In this 200-year period, successive shorter stages will be marked out, also forced by monetary reforms that were very frequent at that time. The 4th and 5th centuries are the time of a diametrical change in the Roman monetary system. Provincial mints stopped working and „local” mints began to operate in their place. At that time, almost 200 mints were working in full swing, spread over the vast territory of the Roman state. In Moesia and Thrace, coins were supplied at that time in numerous Balkan mints, e.g. in Serdica, Sisici, and in Italy’s Ticinum and Milanum, but also in Mints of Asia. We have relatively numerous coins from Nicomedia, Thessalonica, or Cyzicus, Sirmium and Constantinople. And in western mints they arrived in very small quantities, their quantity is actually symbolic. After the monetary reform of 308, huge amounts of „bronze” coins were introduced to the market, a small denomination that literally flooded the entire Roman state (large part of Europe). Each part of the Roman Empire had features unique to itself.

However, the scale of this phenomenon can be observed only recently, due to new research methods. Metal detectors were commonly used during research, because only in this way it is possible to register coins with a small diameter and thickness of the mint disc. The new methodology of excavation research influenced not only the quantity, but also the value of the coins found, because thanks to this, hitherto unknown types of coins from the 4th and 5th centuries are recorded.

All the above events and factors had a colossal impact on the diversification of monetary circulation in individual provinces. This also applies to the coinage of Moesia and Thrace. These differences should be extracted, each time justifying their causes and consequences, paying attention to local elements, characteristic of specific areas. Being aware of the differences between these areas, it was decided to treat them together in this project. The reason for this is that the monetary circulation in these areas was very close to each other in the time frame covered by the project. In addition, the demarcation of the Thracian and Moesian areas is, firstly, debatable, and secondly, changing over time. Let us also remember that while in the 3rd century the monetary situation was relatively clear, in the 4th-5th century it became more complicated due to changes in circulation in the empire caused by annual monetary reforms.

The project will include finds of provincial and imperial coins from the 1st-5th centuries. The basis will be a database of finds that have never been included as a key phenomenon in the characteristics of the monetary circulation of this part of the Empire. The project aims to combine many sources: numismatic and archaeological, unify numismatic data with archaeological and epigraphic sources, supplement with physicochemical analyses.